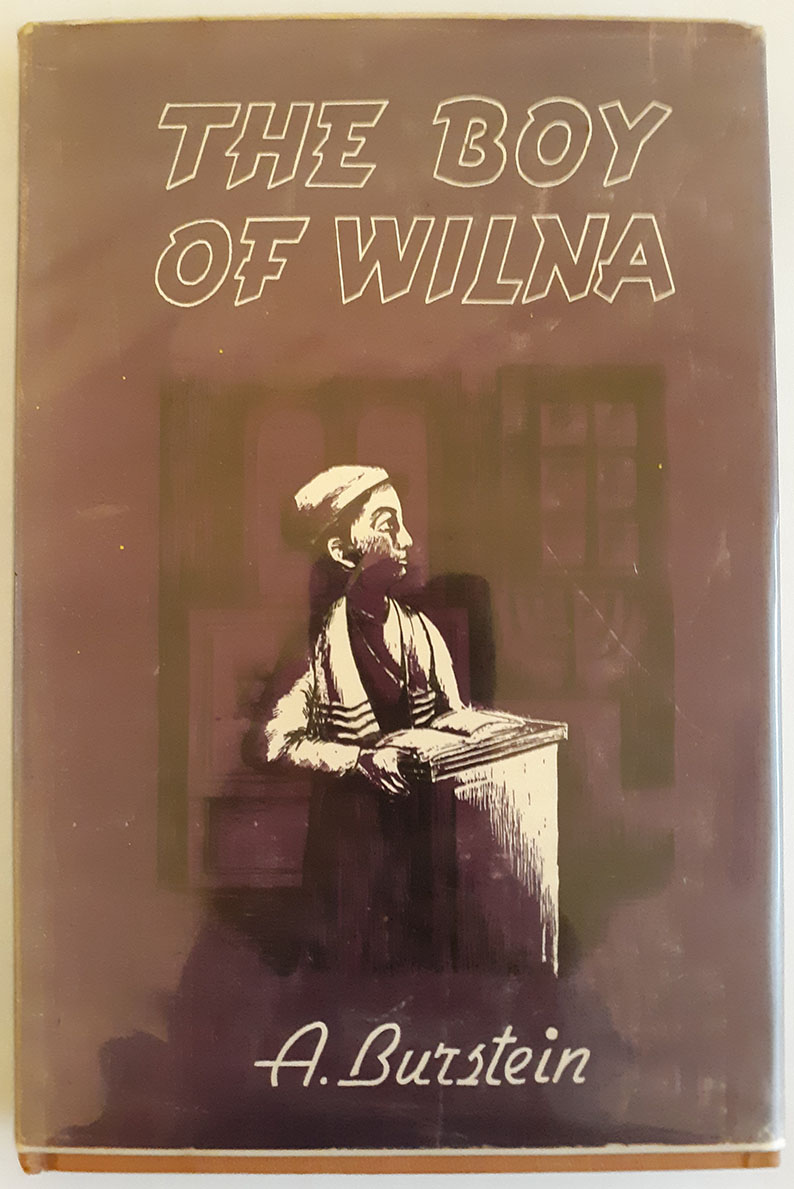

I just finished a children’s book called The Boy of Wilna, written by Abraham Burstein and illustrated by Sol Nodel. It was published in 1941 by the Hebrew Publishing Company in New York and dedicated to “Major Leon Ginsburg, Surgeon and Humanitarian.” I tried to identify Ginsburg but could only find a reference in an American army nurse’s account from 1944. She was serving at the Third General Hospital in Aix-en-Provence, Southern France when the famed soldier Audie Murphy was admitted to the officer’s surgical ward. She relates that a “Major Leon Ginsberg” was a surgeon in that ward and treated Murphy’s wounds.

My particular copy of this book was presented by The Merlin Family Circle to The Ellen Rita Pousner Memorial Library for Children at Congregation Beth Jacob in Atlanta, Georgia. Ellen Rita Pousner’s mother, Rose Maziar Pousner, was a founding member of The Merlin Family Circle, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2009. Ellen died when she was only four years old in 1955 and her parents set up the library in her memory.

The Boy of Wilna is a fictional story about Elijah ben Solomon (1720-1797), known as the Gaon (Hebrew for “genius”) of Vilna, which is modern-day Vilnius, Lithuania. (“Wilna” is the German spelling). A child prodigy, he grew up to become one of the most revered scholars of the Talmud, Halakhah and Kabbalah in Judaism. Contrary to other rabbis of the time, he encouraged the study of secular fields such as mathematics and astronomy, because he believed that these would help one understand relevant passages in the Torah and Talmud. In addition, his main student, Chaim Volozhin, founded the very first yeshiva (school for formal instruction in sacred Jewish literature) in 1803, starting a tradition which would influence thousands of Jewish scholars over the next two centuries. The Gaon was also a prominent opponent of Hasidism, a movement founded by Israel ben Eliezer (ca. 1690-1760), or the Baal Shem Tov (“Master of the Good Name”), in the Ukraine.

Chapter 1: Elijah Talks

Our story takes place during the Gaon’s childhood, beginning when he is seven years old. By that time he has already memorized the Tanakh, or Old Testament, and surpassed his father Solomon, who has nothing more to teach him. People are amazed at the young boy’s achievements. Little Elijah has attracted quite a following, including two unscrupulous gentiles named Stasz and Vanoff. Learning that the father of this Wunderkind is a wealthy man, they hatch a plan to kidnap Elijah and demand a ransom. They belong to a class of gentiles who speak fluent Yiddish and pretend to be Jews in order to commit crimes against the Jewish people, who have no weapons and can’t rely on the police for help. On the Sabbath, Stasz and Vanoff mingle with the Jews attending the great synagogue of Wilna. At only seven, Elijah delivers the sermon and receives resounding applause at the end of the service. The visiting rabbis tell his father that the boy must be sent to the best teachers and schools. One in particular, Rabbi Abraham Katzenellenbogen of Brest-Litovsk (modern-day Brest, Belarus), suggests sending Elijah to his father, the Rabbi of Kaidan, who would be able to find a teacher for him. Solomon fears parting from his son at such a young age and sending him to a faraway place (Brest-Litovsk is over 350 km southwest from Wilna), but Rabbi Abraham and others persuade him that Elijah is one in a generation, perhaps a century, and must expand his learning for the sake of Israel. Solomon can’t disagree, but his heart is heavy.

Incidentally, the name “Katzenellenbogen” may seem fictional, but it is actually the name of an old Jewish family whose members were and are still found in Italy, Poland, Germany, Alsace, and also in America. It derived its name from the locality of Katzenelnbogen in the Prussian province of Hesse-Nassau. Abraham ben David Katzenellenbogen (ca. 1700-1787) was a real person. Abraham met Elijah in 1726, when the former was staying with his father-in-law in Wilna. Abraham took young Elijah to his father’s house in Kaidan (i.e. directly there instead of stopping in Brest-Litovsk as in Burstein’s book) and kept him there several months. As rabbi of Slutsk, Abraham signed the 1752 proposition to excommunicate Jonathan Eybeschütz, who was accused of being a Sabbatean (i.e. a believer in the false Messiah, Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676), who attracted a vast following in the Diaspora though he later converted to Islam). In 1755, Eybeschütz appealed to Elijah (then rabbi in Wilna), who wrote back that he supported Eybeschütz. However, in his typical humble fashion, Elijah doubted that his words would carry much weight since he was only thirty-five. This was in spite of the fact that Elijah was already considered the greatest of his generation, which included many older Torah luminaries.

Chapter 2: The Journey

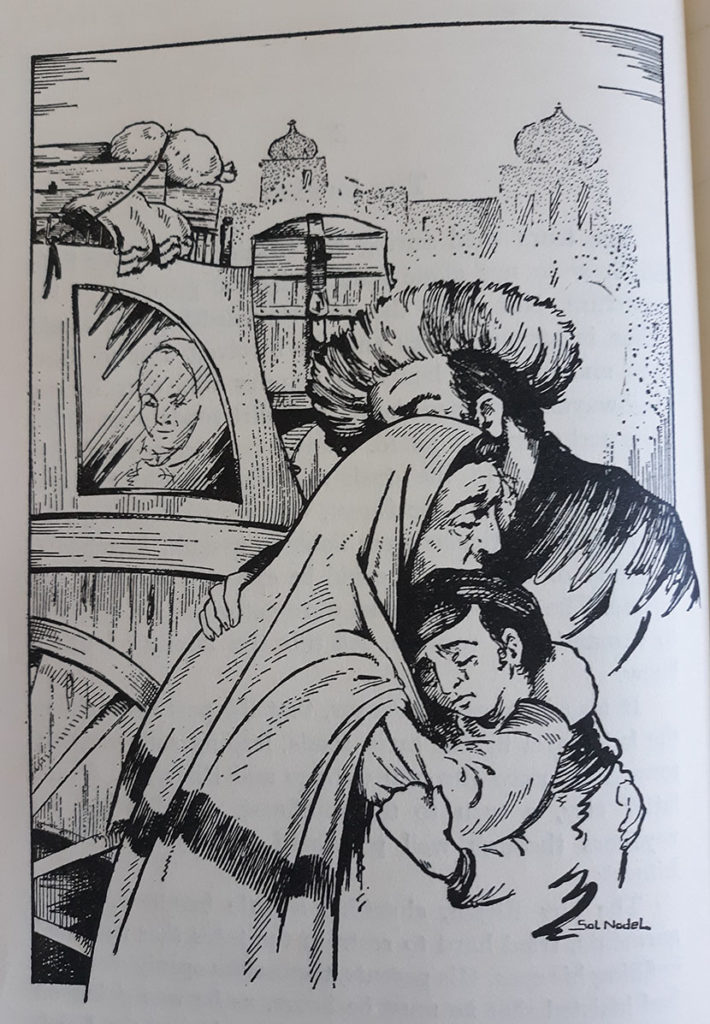

Elijah has a tearful parting from his parents, but they tell him that he will be honoring the Lord and that learning is the greatest mitzvah, or commandment. His parents are also concerned about the journey itself, because traveling in 18th century Eastern Europe was dangerous for everyone, especially Jews, who were often attacked by highwaymen or kidnapped for ransom. Therefore the driver is accompanied by an armed bodyguard and they arrange to stay at Jewish inns along the way.

Their fears prove well-founded, for three horsemen later catch up with them and hold them at gunpoint, but before the criminals can complete their mission, two other riders chase them away. These happen to be Stasz and Vanoff, in the guise of rescuers. They promise to “look out” for the travelers in case the highwaymen come back. Based on Elijah’s advice, the party takes further precautions during the journey and it pays off in the end when Stasz and Vanoff return to attack the carriage. Fortunately the guard’s pistol scares their horses.

Chapter 3: Lonesome Boy

By the time they finally arrive in Brest-Litovsk, Elijah is feeling very homesick. He brightens up a little when he meets a boy about his age named Asher, who is the younger brother of one of the passengers. Asher goes with Elijah to the home of Rabbi David Katzenellenbogen of Kaidan. The rabbi’s wife welcomes Elijah, who starts crying anew at the memory of his parents, and brings him in to see the rabbi. When Asher departs, Elijah feels alone again. Rabbi David suggests that he first get something to eat. While Elijah eats his meal, Rabbi David speaks with his son about the events of the journey. He laments the recent kidnappings of Jewish children in Poland. Sometimes the parents give all their possessions in ransom but never see their little ones again. Both rabbis are concerned that men will attempt to kidnap Elijah again. “A child like this,” says Rabbi David, “is more precious than all wealth of gold and jewels. Israel will be saved not by money but by knowledge of the Torah.” Later Elijah voices a similar belief, that it is the duty of every Jewish boy to become a scholar.

I would like to pause here for a moment to consider this concept: that the hope of Israel lies in deeper understanding of the Torah. After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D., the Jews were bereft of a way to offer sacrifices to God and fulfill many of the commandments in the Torah. Over the centuries this searching developed into a passion for learning as a way of obeying God. Study replaced the physical offering on the altar. And since sacrifices brought atonement, Torah study could help fill that role and bring about the salvation of Israel and the coming of the Messiah. Before the re-establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the Jews in Eastern Europe and around the world were still living in exile. They didn’t know when or how God would redeem them, but they believed that the answer lay in Torah study and observance. That’s why someone like Elijah was so important. Even if the historical Gaon was never in danger of kidnapping, his family and community would still have treasured him as a potential savior for his people. Indeed, every Jewish boy was supposed to strive towards excellence in learning. While most were of average ability, there were a few like the Wilna Gaon who possessed brilliant intellects. Their appearance on earth brought hope to the Jewish people suffering under oppressive gentile governments and their writings added to the scholarship surrounding the Torah.

Chapter 4: Life in Brest-Litovsk

Speaking of oppressive gentile governments, our friend Asher enlightens Elijah about life in Brest-Litvosk. Apparently the Jewish community is responsible for providing supplies (meat, fish, oil, candies, paper, wax, etc.) to the army when it passes through the city. The government doesn’t reimburse the Jews for this contribution, which fortunately only occurs once or twice a year. As a result, the Jews keep big stores and warehouses stocked year-round. To do this, the kahal collects taxes on the community for selling items like salt and meat, for running mills and taverns, for bringing dowries in marriage, and for operating trades like carpentry. The kahal originated in ancient Israel but this particular tax-collecting variety developed in the 16th century in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where Elijah lived. They usually had 22-35 members and their executives were elected by the community. Asher relates that his father was made superintendent of the local kahal and keeps accounts of all the taxes. Historically these kahals became the autonomous governments for the Jewish communities in Poland and Lithuania. As Asher explains, they paid for and administered all aspects of the community, including commerce, hygiene, sanitation, charity, education, kashrut (dietary laws), the rabbi and judges, the synagogue, and the mikveh (ritual bath). They could even excommunicate people. But by Elijah’s time, many Jews wanted to do away with the kahal because the members were abusing their authority. The Imperial Russian government officially abolished the institution in 1844 in most of the empire except for the Baltic region. Thereby the Jewish communities lost much of their autonomy and could only govern religious and charitable matters.

Significantly, Asher also tells Elijah that, in addition to the taxes, the Jews must give gifts to the papal nuncio (an ambassador from the Pope in Rome) whenever he visits the city. The boys look over at the cathedral. Elijah wants to get closer, but Asher warns that sometimes the children and adults coming from that church get angry at Jews. Elijah asks if all the goyim are like that. Asher admits that most are all right and that Jews are even allowed to sue gentiles in court.

Chapter 5: The Nuncio

Several weeks later, the rabbis and leaders of the community gather to discuss the imminent arrival of the papal nuncio. Rabbi David permits Elijah to attend. Rabbi Abraham opens with a review of the “precarious” situation of the Jews living in the region, who must “support the army, pay excessive taxes, rule our own community, and remain at peace with the ruling religion.” He explains that although the Jews have given gifts to the papal nuncio and cathedral officials in the past, many community members now feel that it’s too much of a burden on top of all their other contributions. His father, Rabbi David, counters that Jews may be equal citizens before the law, but they shouldn’t rely on that to save them if they stop giving homage and presents to the gentiles, who view it as their right. He reminds the group of what happened to the Jews in Spain, who were expelled in 1492 after a “Golden Period” of relative security. He warns that it is dangerous to stop giving the offerings. The others agree in spite of their reservations.

On Thursday morning, Elijah hears trumpets blaring outside. He starts to go to the window, but Rabbi David tells him to come back. “It is the nuncio’s party,” he explains. “They pass near our Jewish quarter. In the past Jews watching the procession have been accused of spying and doing disgraceful things, and there have been trials and executions as a consequence. All Jews living near the nuncio’s route will shutter their homes and remain utterly silent until all have gone by. We shall have our hour later, at the cathedral.”

After the nuncio’s company passes by, the Jews emerge from their houses to form their own procession. They have placed a hogshead (large wooden barrel) filled with sugar on a cart along with a bunch of smaller packages. Apparently the kahal of Brest-Litovsk always presented a hogshead of sugar, which was very expensive in those days, to the visiting dignitary from the Vatican.

On the steps of the cathedral, the local priest welcomes the papal nuncio, who praises him and his flock for their loyalty to the Church and hopes that soon all non-believers would be converted. The non-believers themselves then step forward to give a welcoming speech and present the sugar and other gifts to the church officials.

The papal nuncio tells the Jewish assembly that he is happy to receive the gifts, but that he (and God Himself) will always “weep for you, in that you have hardheartedly set yourself against the true faith.” Until the day when God reveals the truth to them, the Church will consider the Jews as their “poor benighted brethren.”

The nuncio then asks to meet the Wunderkind from Wilna. Rabbi Abraham is hesitant to allow this, but Elijah obeys. The nuncio asks Elijah if he has ever considered studying other religions in order to ascertain which is nearest the truth. Again the rabbis are worried about what Elijah will say, but he acquits himself well and answers respectfully. However, he is frightened when the nuncio says he hopes to see him in Rome one day, where he can teach the boy “some of the matters in which your present teachers may be deficient.” The clerk declares that the Church needs “bright boys” like him. And the priest says that anyone who studies the teachings of Catholicism “must surely turn to us for salvation.” Elijah shrinks back from these men who seem to want to make him a meshumad (lit. “destroyed one”), one who has abandoned his faith.

On the way home, Rabbi David talks with his son about the nuncio’s interest in Elijah. They are worried that some of the Catholics “in their blind devotion to their Church” might steal the boy for the sake of Rome. Rabbi Abraham says that the Catholics often look on even the converted Jew with hostility. “The convert gains very little,” he concludes, “except that in four generations his descendants may not be molested.” After taking leave of the members of the procession, Rabbi Abraham suddenly pushes his father and Elijah inside the house. He says he thought he saw some of the church people eyeing the boy. He was right: Stasz and Vanoff were lurking about.

Chapter 6: Kidnapers

The next day Asher invites Elijah to visit his Talmud Torah. Rabbi Abraham comes along and gathers a group of older boys preparing to become rabbis. He informs them of the danger surrounding Elijah from criminals and zealous Catholics and asks for their help. About twenty volunteer, but they have no weapons. Rabbi Abraham cautions against arming themselves which might alarm their Christian neighbors, but he does suggest that they can act as bodyguards. Unfortunately the boys get a bit too excited to play soldiers and start parading as guards with wooden sticks. Alarmed, Rabbi Abraham tells them to be more discreet or they will incite the gentiles, who look on the Jews as “petty tradesmen, students, weaklings, slightly inferior testimonials to the greatness of their own religious teachings.”

Some of the rabbinical students follow Elijah and Rabbi Abraham home at an unobtrusive distance. Suddenly, while everyone is distracted by the loud, humorous quarreling of Ezekiel and his wife Shprintze, two men on horseback approach. Dismounting, they sneak up on the rabbi, knock him unconscious and grab Elijah. Fortunately the kidnappers get tangled up with Ezekiel, Shprintze, and their vegetable cart. The students are able to chase away the assailants. Rabbi Abraham praises the couple for quarreling at that moment and inadvertently saving “the crown of Israel’s youth.” He believes that God has intervened to protect Elijah.

Chapter 7: Life in Kaidan

Though God has protected the boy so far, Rabbi Abraham asks his father and mother to leave Brest-Litovsk and return to their home in Kaidan. They must get Elijah to safety. Again they take safety precautions for the journey, this time with two armed drivers and an armed horsemen riding behind the coach. This will be an even longer journey, as Kaidan (modern-day Kėdainiai, Lithuania) is over 400 km north from Brest-Litovsk. As they depart, Elijah reflects on the “strange and perilous incidents” he has experienced for the sake of Judaism. He believes that study is equivalent to all the other virtues, as “knowledge makes men free, just, helpful, and righteous.”

When they arrive in Kaidan, a large crowd welcomes them, led by the elders of the community. Elijah feels left out again at first, but then the people surround him with smiles and greetings, which encourages him. He also meets his new teacher, Moses Margalit (also called Margolies). Moshe ben Shimon Margalit (ca. 1710-1780) is best known as the author of a dual commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud, which had been almost entirely neglected for centuries. Margalit influenced the Wilna Gaon’s view that since the study of Torah is the very life of Judaism, it must be conducted in a scientific and not merely a scholastic manner. In addition to the warm welcome he receives, Elijah starts to attract matchmakers, including the synagogue president on behalf of his granddaughter, who want to marry the brilliant boy into one of the local families. Rabbi David puts a stop to it but he and Elijah get a good laugh out of it all the same.

Chapter 8: The Student

Elijah remains in Kaidan for a few years to continue his study under Moses Margalit. At age nine he runs out of things to learn, so the rabbis introduce him to the Kabbalah. He is not impressed, however, and decides that it’s time to study secular subjects. Rabbi Moses is hesitant at first and is afraid that Elijah might turn away from Judaism if he delves too deeply into other fields, but Elijah assures him that this will never happen. So Rabbi Moses gives him a book on astronomy and then one on botany.

Wanting to encounter nature firsthand, Elijah starts taking walks in the country. Then he decides to seek further information from the farmers. Sadly the peasants have no desire to teach him. They drive him away and curse him for being a Jew. It’s not really surprising, though, as most of the peasants in Poland and Lithuania (just as in Russia) were uneducated and impoverished, living in filth with their animals and children. Serfdom had existed in the region for centuries. Peasants had few rights. It was difficult for them to own the land or leave their lord’s land. By the 18th century, almost all of a peasant’s time could be requested by the lord. Though reforms had begun, Poland did not abolish serfdom until 1864. Russia did so a few years earlier in 1861. To a Jewish boy who valued learning and ritual cleanliness, the lives led by his gentile peasant neighbors would indeed have been revolting.

Next Elijah wants to learn mathematics. As Rabbi Moses is not well versed in the subject, he mentions that the new priest in Kaidan has such knowledge. Elijah immediately wants to study under the priest, but both Rabbi Moses and Rabbi David view it as near blasphemy. They compromise by allowing Elijah to visit the church only if accompanied by Rabbi Moses. The priest, Father Zema, happens to be from Wilna too and had been in Brest-Litovsk on the day of the papal nuncio’s arrival. Though Father Zema would prefer to speak about the Catholic faith with him, he agrees to confine their discussion to mathematics.

Over time Father Zema grows to respect the boy’s wisdom and asks him for advice in parish matters. One day he even visits the rabbi’s house to speak privately with Elijah. This is an unheard-of event in the Jewish community. The rabbis are afraid to leave the boy alone with the priest, but Father Zema assures them he will not try to convert him. Instead he asks Elijah to help him compose a letter to Rome asking for a promotion. After helping the priest, Elijah tells the worried rabbis what it was all about. Still they are greatly distressed that the Church might try to steal Elijah. The boy declares that he would never convert, even under pain of torture, and promises that he will no longer seek any non-Jewish help for his non-Jewish studies.

Two weeks later Elijah receives a letter from Father Zema thanking him because his request for advancement was successful. It would have been a happy moment, but Elijah recognizes the messenger as Stasz.

Chapter 9: Friends and Parents

The Jewish community decides to start keeping watch over the boy again. Meanwhile rumors spread about his visit with the priest and his secular studies. The people fear he might become an apostate like other young Jews. They become especially concerned when they hear of his interest in anatomy and medicine. What if he becomes a goyishe doctor?

Even Elijah’s parents travel from Wilna to make sure that their son is safe and staying true to Judaism. They ask him to stop studying medicine and focus on the Torah. When they see that Elijah goes around with a bodyguard and hear about Stasz working for the local church, they demand that Elijah come back home with them. Rabbi David tries to convince them that Elijah is not in danger anymore and that removing him now would destroy all that he and the other rabbis have built up, but the frightened parents insist on taking their son home.

Chapter 10: End of Danger

Just at that moment, the student bodyguards apprehend Stasz and Vanoff outside the rabbi’s home. Like the Maccabees centuries before, the young Jewish scholars stand like “angels of vengeance,” prepared to defend their community from the gentile ruffians. And Stasz and Vanoff, remembering the stories told in their youth about Jewish assassins who would never hesitate to shed gentile blood, stand quaking in their boots. Although it’s illegal for a Jew to act as a policeman or judge, particularly against church servants, Rabbi David decides to risk it all in order to protect Elijah, who might one day save his people Israel.

Stasz and Vanoff admit that they once led a life of crime, even attempting to kidnap Elijah, but they say that they’ve gone straight and now work for Father Zema. They ask the Jews to call the priest, who will vouch for them. Father Zema arrives and corroborates their story. He relates that they came to him several months ago, asking for bread, and he encouraged them to confess their sins and turn over a new leaf. The priest also assures the Jewish community that no harm will come to Elijah from these two men or anyone else. At this the crowd’s hostility subsides.

“I am honored,” says Father Zema, “to be in the presence of so much learning. Though I hope to see all men in the fold of my faith, I can recognize knowledge and honest belief in everyone. I am sorry that so often do fellow priests and coreligionists speak ill of the people of Israel. We are all sons of the one God. As to Elijah, I feel certain that his name will be remembered on earth when my own is utterly forgotten.” Elijah’s parents are thrilled to hear their son praised by a priest of the ruling religion. They decide not to take the boy away from Kaidan. Father Zema gives Elijah a book on mathematics by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), who died four years before the Gaon was born. He also promises not to give the boy any books which might lead him away from Judaism. The students cheer him on. To those who had “suffered mentally under the lash of a dominant faith that forever demanded their immediate conversion, this was almost the sign of the millenium.” (This refers to the Messiah’s reign of peace, lasting 1,000 years, which will precede the Last Judgment and the afterlife). Stasz and Vanoff appoint themselves as Elijah’s new bodyguards (“protective angels–with the features of devils”), while fifty Jews escort Father Zema back to his home.

Conclusion

Burstein concludes the book with a brief biography of Elijah’s later life. “Great is a people that can produce such men,” he writes. “May his counterpart yet appear in the parlous age through which Israel is passing!” This may be a reference to the Holocaust, which had begun in the 1930s with the Nuremberg Laws and early concentration camps but accelerated in 1939-1941 with the Nazi occupation of Poland (home to around 3.5 million Jews). I don’t when when in 1941 this book was published, whether before or after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet occupied zone in Poland, but neither Burstein nor his readers could have foreseen how complete would be the destruction of Jewish life in this region.

Vilna

Before World War II, the Gaon’s hometown of Vilna was one of the largest Jewish centers in Europe and was known as the “Jerusalem of Lithuania.” The Nazis captured it on June 24, 1941. They set up two ghettos for the Jewish population in the old town center. They “liquidated” the smaller ghetto by October 1941, but the larger one lasted until 1943, though groups of people were regularly rounded up and deported to camps. Between June 1941 and July 1944, the Nazis and their collaborators murdered over 75,000 people, most of whom were Jewish, in Ponary, which is about 10 km south of Vilna.

Brest-Litovsk

The Nazis captured Brest (Polish: Brześć) from the Soviets on June 28, 1941. In July they murdered about 5,000 Jewish men. In December, the Nazis moved the remaining Jewish population (about 20,000) into the Brest ghetto. They “liquidated” it in October 1942. Between May and November 1942, the Nazis murdered around 50,000 Jews (most from Brest but also from other ghettos) in the forest of Bronna Góra (Brona Gura) near Kartuz-Bereza (Byaroza, Belarus). When the Soviets recaptured Brest in 1944, they found less than ten Jews still alive.

Kaidan

The Jewish community of Kėdainiai (Yiddish: Kaidan) had existed for 500 years. On August 28, 1941, the German police battalions, with the aid of the local Lithuanians, massacred the entire Jewish population (about 3,000 people).

In all, more than 90% of Poland’s Jews (3 million people) and over 95% of Lithuania’s Jews (about 195,000 people) would be murdered by the end of the war. Hundreds of years of Jewish culture were erased with the destruction of human lives and physical things like homes, synagogue buildings, prayer houses, schools, prayer shawls, Torah scrolls, and books both sacred and secular. In their place were left piles of clothes, shoes, suitcases, eyeglasses, hair, teeth, and jewelry…and ashes and bones. Entire Jewish towns vanished from the map, replaced with stone memorials. Whole branches of people’s genealogies were blotted out, leaving the survivors to wander around in the emptiness. Though there are still small Jewish communities in Eastern Europe, we will never see the same kind of life that Burstein describes in The Boy of Wilna or that Sholem Aleichem writes about in his beloved stories. Even amidst persecution from all sides, often crushed with poverty, and knowing that they were in exile from their home in Israel, these people lived vibrantly for the sake of the Lord. Let us never forget them.

References

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49395558/ellen-rita-pousner

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/45669355/rose-pousner

http://www.audiemurphy.com/documents/doc038/CarolynPriceRyanRecollections_12Feb73.pdf

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5651-elijah-gaon

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/9238-katzenellenbogen

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/9117-kahal

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/10840-millennium

http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/vilna/during/ponary.asp

http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Brest

https://www.jewishgen.org/databases/Belarus/brest.htm

https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/bereza93/ber179.html

https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/kedainiai/Regional_Museum.html