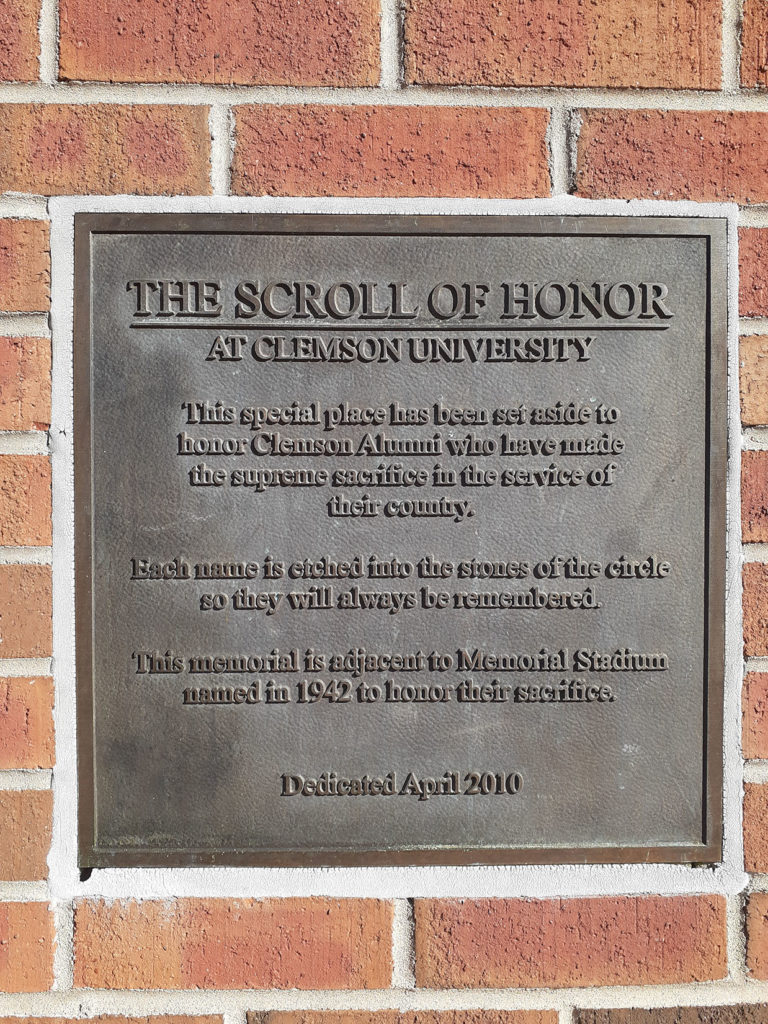

On December 9, I visited the Scroll of Honor Memorial on campus to take some pictures for my thematic research collection, “Service and Sacrifice: Clemson Men in World War II.” While I had walked through Memorial Park many times during the semester, this was the first time I had stopped by the Scroll of Honor. It was a perfect day to visit: clear and sunny, not too cold, and quiet.

The entrance is impressive, but the real moment comes when you turn left towards the barrow, which rises up like an old burial mound. You feel that you are about to enter a sacred place. You approach reverently, as if afraid to disturb the dead. The fallen are not buried here, of course, but you can sense their spirits.

From a distance, it appears that the barrow is ringed with ordinary stones, but as you draw near, you start to make out names and class years on the stones. Each one represents a young man who was killed in one of the many wars of the past century: World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, the Middle East. You will also notice that the names are engraved randomly on the stones, symbolizing the fact that there is no pattern to death in war.

I had come to photograph the memorial for my project, and I wasn’t sure where to begin with the stones, so I simply started walking clockwise around the barrow, looking for relevant class years. The dappled sunlight created a beautiful setting.

As I became accustomed to the sheer number of stones, I began to pick out names that I knew. It wasn’t long until I found Henry Leitner’s stone. Along with thousands of Americans, Leitner was taken prisoner by the Japanese in the Philippines in spring of 1942. He survived the death march to the prison camp and reunited with fellow Clemson graduates Manny Lawton, Otis Morgan, Ben Skardon, Bill English, Francis Scarborough, and Martin Crook. He became especially close to Lawton during their long imprisonment in the Japanese camps. In December 1944, the Japanese moved the prisoners to Manila and loaded them into the dark, suffocating hulls of “hell ships” for evacuation to Japan. American planes attacked the unmarked ships, not realizing that they carried prisoners. Hundreds of prisoners died in the bombings, while others succumbed to starvation, dehydration, cold, and illnesses such as dysentery and pneumonia. Their ship arrived in Japan with only 400 survivors out of about 1,600. Tragically, Leitner soon succumbed to pneumonia. While Lawton survived until the Japanese surrender, Leitner’s death filled him with grief.

I also found Ben Robertson’s stone. A graduate of the Class of 1923, Roberston became a war correspondent during World War II. He went to England in 1940 and worked with Edward R. Murrow covering the German bombing of London, known as “The Blitz.” The Clemson community looked to him for guidance during the prewar years and especially when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. During 1942, Robertson traveled extensively for the New York paper PM and the Chicago Sun in the Pacific, Asia, and North Africa. In addition to being a journalist, Robertson also wrote three books: Traveler’s Rest (1938), a historical novel based on his ancestors’ experience in South Carolina; I Saw England (1941), about his wartime experience in Britain; and Red Hills and Cotton: An Upcountry Memory (1942), which is his best-known book.

On February 22, 1943, while en route from the United States to his new job as chief of the New York Herald-Tribune’s London bureau, Robertson was killed in a plane crash in Lisbon, Portugal. Clemson mourned his death and held a funeral service in the College Chapel on April 18, 1943. A Liberty Ship, the SS Ben Robertson, was named after him in 1944.

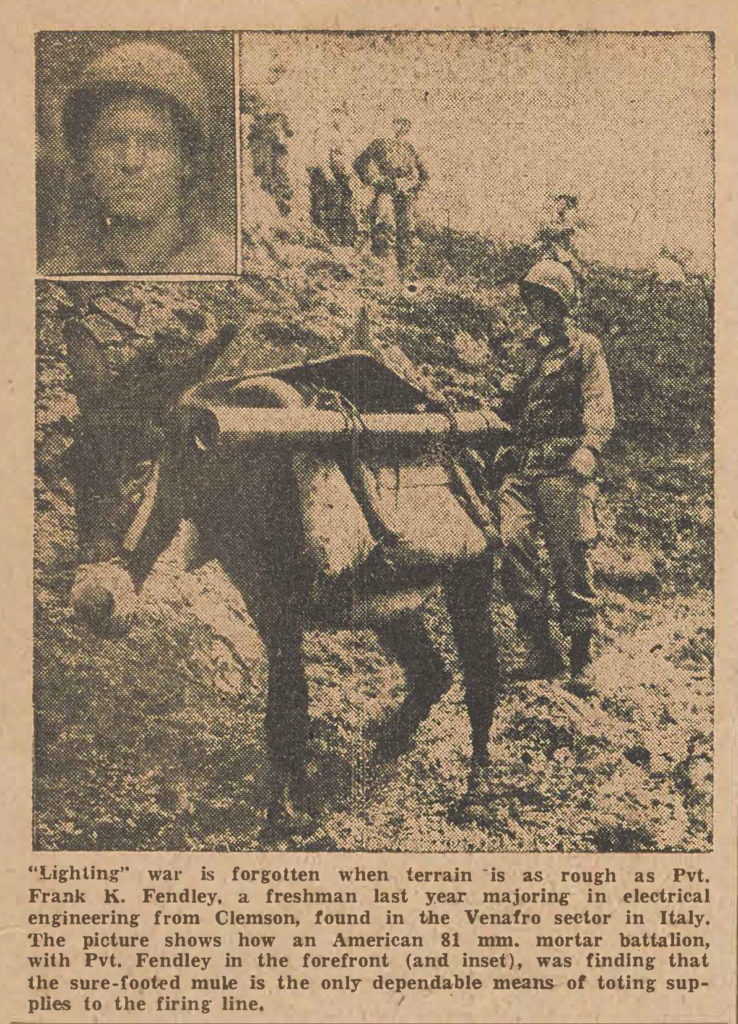

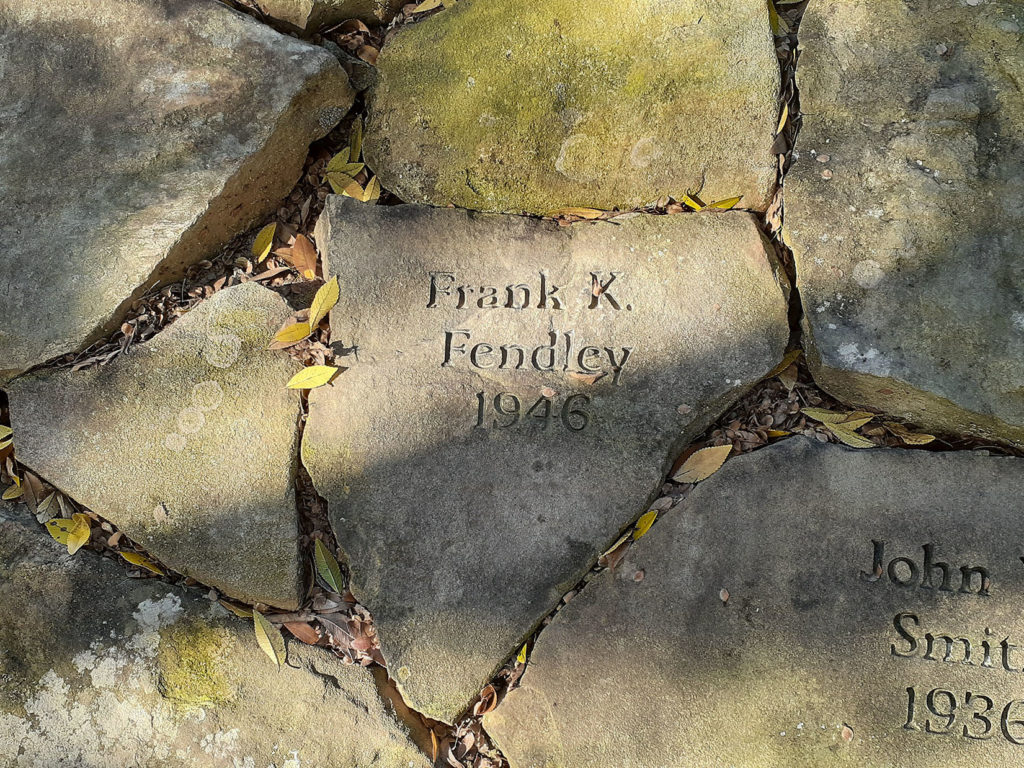

Finding Frank Fendley’s stone was particularly moving. I discovered Fendley while looking for wartime articles in the Clemson student newspaper, The Tiger. A captioned photograph printed in the February 24, 1944 edition of the newspaper shows Fendley as a private, slogging through the mud behind a supply mule, along with his mortar battalion in the Venafro sector in Italy. From autumn 1943 to the spring of 1944, Venafro was the scene of bitter fighting between the Germans, entrenched in the mountains to the north, and the Allies, along the Gustav Line, during the Battle of Monte Cassino. According to later articles in The Tiger, Fendley became a highly decorated soldier during the Italian campaign, reaching the rank of Staff Sergeant. He was awarded the Purple Heart in September 1943 after being wounded in the battle for Rome. Sadly, he was killed in action a year later on September 18, 1944.

As I made my way around the barrow, absorbed in looking at the names, I was surprised to discover a solitary wreath that had been laid above the stones. It was a surreal feeling, knowing that someone (a relative or a volunteer from Wreaths Across America?) had come before me and left this token of remembrance. I looked around: there were no other signs of a human presence here. Just this wreath. I wondered which stone it was meant for. Perhaps John H. Schroder, Class of 1921, or Hampton N. Dent, Jr., Class of 1941? These are the two closest stones, and the class years suggest that both were killed during World War II. Schroder would have been older, likely a major or colonel in his 40s, while Dent, Jr. would have been young, only in his 20s.

Even though I had come to the memorial for my project, it turned out to be a special experience for me. On that sunny, peaceful December afternoon, I felt a sense of reverence in the presence of the names. These were real human beings who lost their lives, many in the prime of their youth. They were husbands, sons, and brothers who left behind grieving families. Not all of them fell heroically in battle; some died in accidents in the States before ever being deployed or, like Henry Leitner, perished as prisoners of war, victims of malnutrition and disease. May they rest in peace.